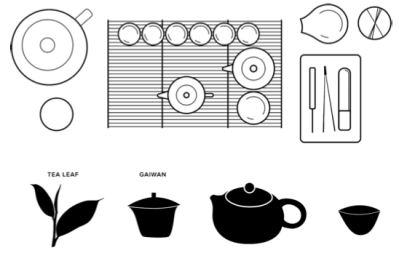

Here’s another article that I’ve translated from the 中国茶经, the “Chinese Tea Bible”, on selecting tea utensils. Students of gōngfuchá will not find any revolutionary information in this translated article, and online videos would be a better tutorial for beginners, but there are a few linguistic curiosities here. Most notably, the words 盖碗 [gàiwǎn] 盖杯 [gàibēi] and 盅 [zhōng] all appear in this article, and yet they can all be used to refer to the same object.

Gàiwǎn, literally “lidded bowl,” is the term most familiar to Western tea aficionados referring to the brewing/drinking apparatus shown at left. According to this article, a gàibēi (“lidded cup”) is the same object, but the name reflects its use primarily as a drinking vessel rather than a brewing vessel. It has also been asserted that “gàibēi” would indicate a vessel smaller than a gàiwǎn, which would sync with the English usage of “cup” and “bowl.”

Gàiwǎn, literally “lidded bowl,” is the term most familiar to Western tea aficionados referring to the brewing/drinking apparatus shown at left. According to this article, a gàibēi (“lidded cup”) is the same object, but the name reflects its use primarily as a drinking vessel rather than a brewing vessel. It has also been asserted that “gàibēi” would indicate a vessel smaller than a gàiwǎn, which would sync with the English usage of “cup” and “bowl.”

Recent Comments: